Last week I posted about how national governments on both the right and left use schools as a weapon against minority ethnic groups, whose children are forced to live their lives on the frontline of concerted government efforts to ‘assimilate’ them. But what happens when Indigenous people fight back against education policies designed to destroy their cultures and identities? Here’s the story of one such case, based on my own research on Indigenous schooling and revolutionary nationalism in twentieth-century Mexico.

The Mexican Revolution (1910-1940) was an era of tremendous upheaval and dramatic social, political, economic and cultural change. After the ‘armed phase’ of anti-regime rebellion and revolutionary civil war came to an end in 1920, the victorious revolutionary factions embarked on a twenty-year project of radical state- and nation-building.

Agrarian reform, industrialization, and education programs were promoted with a view to ‘developing’ Mexico’s predominantly agrarian and extractive economy, liberating its people from poverty, and unifying the diverse population around nationalist ideals and a glorified mestizo (mixed-race) identity. In order to achieve the latter goal, education policy in particular was geared towards the political, cultural and economic assimilation of the approximately thirty percent of the population then living in Indigenous communities into the mestizo Mexican mainstream.

Such efforts have often been lauded as bringing literacy and ‘progress’ to rural Mexico’s most forgotten corners. And, in some areas, Indigenous people did welcome the arrival of teachers in their communities.

But in other areas, Indigenous people who had managed to hold on to high levels of cultural, political and territorial autonomy rejected government programmes that offered them ‘education’ only at the cost of their distinct beliefs, languages, and ways of life.

Eventually, a mixture of passive resistance and violent opposition on the part of many Indigenous communities forced important changes to national education policies, and led to the emergence of a new generation of Indigenous teachers who became important local leaders in their own right.

Education Policy and Indigenous Resistance in 1920s Mexico

Mexico’s Secretariat of Public Education (SEP) was the federal body charged with spearheading the educational side of the Mexican Revolution’s transformative program. Heavily influenced by the ideas of US social scientists, SEP policy makers saw the problems of Indigenous communities as the result of their physical and cultural ‘isolation’ from markets, capital, and mainstream society.

They regarded ‘primitive’ Indigenous identities and ways of life as a barrier to their incorporation into a ‘modern’ nation-state conceived of as inherently ‘mestizo.’

In response, they promoted a model of education that demanded Indigenous children give up their traditional languages, religious beliefs and customs in favour of the national language – Spanish – and new, ‘revolutionary’ and inherently mestizo ‘national’ values.

While some Indigenous communities welcomed the new opportunities that the government’s education programmed brought with it, others opposed it because could not afford to contribute to the construction and upkeep of schools; because they disliked self-important teachers or suspected them of being ‘Protestants;’ or because they simply couldn’t afford to lose their children’s help in the home and in the fields.

Others were offended by the frequent meddling of teachers in local politics and their promotion of the physical colonization of Indigenous lands by mestizo ranchers in order to help spread ‘civilized’ mestizo values. Above all, many Indigenous people refused to give up their distinct identities and practices as a condition for their integration into the new revolutionary nation-state.

Such opposition naturally hardened when teachers and school inspectors tried to overcome it by ‘forcibly removing’ – that is, kidnapping – Indigenous children from their families in order to send them to boarding schools where, distanced from their ‘primitive’ material and cultural surroundings, they could be more easily ‘civilized.’

Such tactics were also used against Indigenous students in the US, Canada and Australia, and against religious dissidents in the Russian Empire. In Mexico, they became common from 1922, first to procure Indian children from peripheral regions for regional boarding schools, and then, from 1925, to be taken away to study at the national Indigenous boarding school in Mexico City.

In recent decades the toxic legacy of ‘residential schools’ has been subject to high-profile debate and soul-searching in many countries. And if you want to know more about it, you should check out my last piece, here:

And also

’s recent Skipped History post, here:But in Mexico, neither the state nor civil society has addressed the historical abuses committed against Indian children by the SEP.

Instead, the idea of Mexico’s rural teachers as noble martyrs in the service of popular liberation from oppression, poverty and ‘backwardness’ remains pervasive.

Understandably, the families of the Indigenous children kidnapped by the SEP often regarded such actions in a less forgiving light. The SEP’s use of ‘forced recruitment’ was also frequently counter-productive, prompting Indigenous parents to refuse to allow their children to attend any kind of government school.

As a result, as the 1920s wore on, SEP officials faced ever greater opposition to their attempts to recruit Indigenous pupils in many different areas of Mexico. Such resistance most often centered on the use of ‘weapons of the weak’ such as foot-dragging, noncompliance, evasiveness, and obfuscation.

But in areas such as the Gran Nayar mountains of western Mexico, Indigenous people also resorted to less subtle methods, including riot, rebellion, and murder.

Radical Opposition to Schools in the Gran Nayar

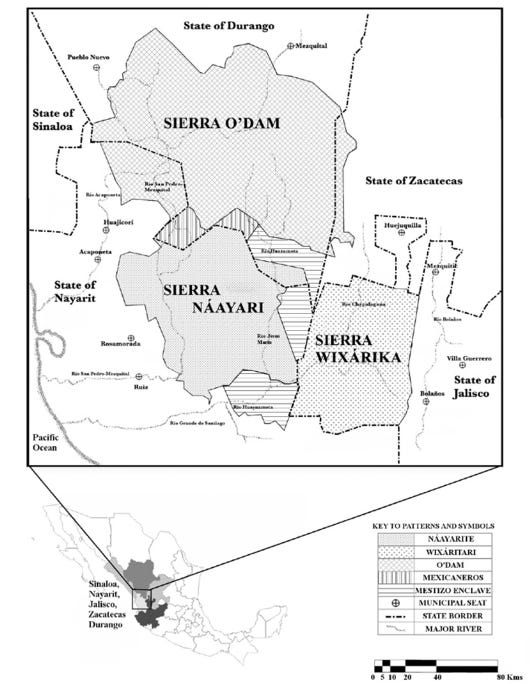

The Gran Nayar is a 20,000 km2 expanse of mountains and canyons that spans parts of the states of Nayarit, Jalisco, Durango and Zacatecas. It is one of Mexico’s most ethnically diverse areas, home to four different Indigenous peoples: the Náayarite (more often known, in Spanish, as Coras), the Wixáritari (Huichols), O’dam (Southern Tepehuanos), and Mexicaneros. Here’s a map:

Into the 1920s, all of these groups held on to distinct identities, extensive, communally-owned landholdings, and a much higher level of autonomy vis-à-vis both church and state than that enjoyed by many of Mexico’s other Indigenous groups. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that their homeland was the venue for some of the most concerted resistance that the SEP’s early assimilatory program faced anywhere in Mexico.

Early local resistance to the SEP was most dramatic in the region’s Wixárika communities. The official in charge of the area’s schools, Diego Hernández Topete, was a close ally of the region’s mestizo elite, whose forebears had seized large swathes of Indigenous territory during the nineteenth century, and who now wanted to make further in-roads into Wixárika territory.

Hernández Topete supported these attempted land-grabs on the grounds that they would bring the Wixáritari into closer contact with ‘civilization,’ advocating that

the lands of the Sierra in which the “Wixárika” lives, be populated by honest and hardworking [mestizo] families, whose resolve, honor and work will infect, forgive me the word, the semi-savage “Wixárika.”

His enthusiasm won Hernández Topete the enmity of his Wixárika hosts, however, who in early 1925 forced the closure of the schools he had established a year before in the communities of San Sebastián and Tuxpan.

In April 1925, the SEP approved the establishment of a replacement school, this time in the Wixárika community of San Andrés. But the teacher appointed to serve there – a Wixárika exile called Antonio Reza, who had been educated in the city of Zacatecas by Catholic missionaries in the years prior to the Revolution – was already a mistrusted and unpopular figure. Reza had arrived back in San Andrés in March, quickly taking control of a communal effort to win government support for local agrarian reform, which riled many of his peers.

This hostility was compounded by the activities of several of Reza’s colleagues, who attempted to forcibly recruit Wixárika children as students for the national Indigenous boarding school in Mexico City by ‘seizing’ them from their ‘lairs,’ with the language they used in such descriptions deliberately implying that Wixárika children were more animal than human.

Perceived as threatening both local landholdings and the integrity of local families, an angry crowd murdered the unfortunate Reza in the grounds of San Andrés’ sacred temple precinct in September 1925, and the local school was permanently closed.

‘Socialist Education’ and Renewed Resistance

Between 1926 and 1931, the SEP’s educative mission in the Gran Nayar was put on hold by the Cristero Rebellion, which saw tens of thousands of Mexican Catholics rise up against the revolutionary government’s anticlerical policies. Despite the religious heterodoxy of the Náayarite, Wixáritari, O’dam and Mexicaneros, many joined the rebels in their fight against the government in order to continue militantly resisting its educational programmes.

It was not until late 1931, with the defeat of the Gran Nayar’s last rebel forces and the appointment of Narciso Bassols as national Education Secretary, that attempts to assimilate the region’s Indigenous population could began again in earnest. Bassols was a Marxist anticlerical lawyer who introduced the doctrine of ‘socialist education’ to Mexico’s federal education system.

Stressing the material origins of Indigenous poverty and marginalization, Bassols’ socialist curriculum focused on teaching the Spanish language, basic literacy and numeracy, improved agricultural techniques, and small-scale industries such as logging and tanning, while ramping up attacks on Indigenous religious beliefs (decried as primitive ‘superstition’), repackaging traditional rituals and celebrations as ‘folklore’ or replacing them with new, ‘civic’ fiestas, condemning the use of alcohol, promoting hygiene and sanitation, establishing local postal services and village cooperatives, and organizing sporting events.

While undoubtedly more sensitive to the problems of Indigenous communities than SEP policies had been in the 1920s, ‘socialist education’ still paid little more than lip service to a colorful and romanticized ideal of the ‘noble Indian,’ while actively seeking to destroy the bases of real Indigenous political and cultural autonomy. In response, the communities of the Gran Nayar turned to tried-and-tested methods of resistance.

Many Náayari and Wixárika families moved their ranches further into the countryside to avoid contact with teachers and school inspectors; parents refused to contribute food supplies or manual labor to schools; and students ran away from boarding schools at the first opportunity.

Meanwhile, in the O’dam communities in the north of the Gran Nayar, resistance to compulsory education programmes took a still more radical form. No schools had been built in this region during the 1920s, and so the opening of a boarding school in the O’dam community of Santa María Ocotán in April 1933 represented most local people’s first contact with the SEP. According to their reports, the local teachers immediately found themselves ‘in a hostile environment, to the extent they have been called foreigners or Government spies, who have come with the deliberate purpose of taking away [from the O’dam] their customs, their religion and their properties.’

By June, local tempers had risen to the extent that the teachers’ very lives were rumored to be in danger, and the school’s headmaster ordered them to stay alert and avoid inflaming tensions by steering clear of confrontations with local people. But such precautions were not enough to avoid a dramatic final rupture with their O’dam hosts six months later, in December 1933, when, in the context of renewed Catholic rebellion in parts of northern and western Mexico, the O’dam warlord Juan Andrés Soto led an armed raid on the unpopular boarding school, destroying it and kidnapping one of the teachers to use as a bargaining chip with the government.

Schools and Indigenous Leaders in the Gran Nayar

In early 1936, Mexico’s most left-leaning president yet, General Lázaro Cárdenas, finally ordered the SEP to abandon the explicitly anti-religious aspects of its programmes, stop viewing rural resistance to schools as no more than a symptom of local ‘backwardness,’ and start defending rural and Indigenous communities against their enemies, including big landowners, conservative military commanders and even abusive local teachers.

The SEP also began to hire more Indigenous people from a wider range of different Indigenous regions to work as teachers in their own communities. Better equipped to mediate between their communities and the state than either local elders or outside officials, many of these young Indigenous teachers soon became influential local political leaders.

When a new boarding school was set up in the Wixárika community of Santa Catarina, for example, among the staff was Agustín Mijares Cosío, son of one of the community’s agrarian representatives. He soon began to aggressively petition various government agencies on behalf of his own and other Wixárika communities, helping to win state recognition of their agrarian claims, as well as military support for their ongoing struggles with the bandits and anti-government rebels still active in the region.

Similarly, in the Náayari community of San Juan Corapan, two young orphans who had been taken away to study at the national Indigenous boarding school in Mexico City now returned home and used their linguistic skills, literacy and experience in dealing with outsiders to push forward the community’s agrarian claims and defend its territory from the incursions of mestizo settlers. Meanwhile, the teachers posted to other Náayari communities began to denounce the ‘iniquitous exploitation’ of local people by mestizo settlers and merchants, demanding the state take action to protect them.

Finally, in the O’dam areas in which the impact of federal schooling had as yet been minimal, the SEP decided to use only teachers who ‘know the language, customs, defects, virtues, etc, of those distant pueblos’, and at the same time establish ‘a special school to which a good number of natives be bought so they can be trained as teachers.’

Conclusions: Resistance is Never Futile

In many parts of Mexico, government schools had boosted literacy rates and fostered the spread of new skills and values, at the same time as dividing communities, weakening distinctive local identities, reducing the vitality of dozens of Indigenous languages, and opening the gates to the mestizo colonization of Indigenous lands across the country.

In the Gran Nayar, however, concerted resistance to racist education policies limited their negative effects on local society, while giving rise to a new generation of young, male Indigenous leaders who had attended government schools but had resisted being transformed into ‘mestizos,’ and instead became resolutely Indigenous leaders well-equipped to negotiate communal demands with the post-revolutionary state.

By manipulating official discourses of ‘patriotism’ and ‘nationhood’ that they had picked up from their teachers, as well as their ability to speak, read and write in Spanish, the national language, these leaders were able to facilitate and legitimize their continued use of subversion, accommodation, evasion, and active, sometimes violent resistance, in defence of the cultural, political and territorial autonomy of their communities – an autonomy that state education policies had attempted to destroy, but which, thanks to their continued resistance, the people of the Gran Nayar continue to enjoy today.

Thank you for reading!

If you made it to here, please consider letting me know what you thought in the comments, and do sign up if you haven’t already - it’s free and it makes writing here regularly feel like it’s worth the effort!

Fascinating post. Really highlights how education is entangled with broader issues about class domination, social power, and imperialism.