Or what passes for education in much of the world, anyway.

In the global north and the global south, from the far east to the American west, today as a hundred years ago and indeed for several centuries now, schools are really prison camps and education is more like ‘re-education,’ deliberately designed to destroy humanity’s endless diversity in a misguided attempt to build ‘stronger’ states and more ‘developed’ economies.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the case of those whom we refer to, often inaccurately, as ‘minorities’: Indigenous peoples, nomads, distinct religious communities and all those broken fragments of previous empires whose homes are now located in someone else’s country. The existence of all such groups is today almost universally regarded as a threat to the cohesion of whatever nation-state they’re unfortunate enough to find themselves living in.

The result is that, all too often, their children are forced to live their lives on the frontline of concerted official efforts to assimilate them.

Efforts in which ideas and institutions that we tend to assume are always enlightened, like schools, education projects and literacy programmes, are used as weapons with which to wipe out distinctive languages, cultures, religions, ways of seeing, of being, and of doing.

State education policies that aspire to nothing less than ethnocide constitute the common ground between democracies and dictatorships, bridge the gap between China and America, span the supposedly unassailable divides between Islamic and Christian ‘civilizations.’

The specificities of cultures, religions, or political ideology are not the point: the thing that unites all of the cases in which schools are used as weapons against the ‘other’ is that such policies are used by nation-states.

The nation-state has, of course, become an increasingly hegemonic form over the course of the 20th century. It now reigns supreme even in places that used to be proudly multi-ethnic, as former empires spanning dozens of not hundreds of ethnicities broke apart and were replaced by smaller polities that aspired to the homogeneous, ‘one people, one state’ model as their end game.

The brutally successful spread of this idea is all too clearly evidenced by the increasingly rapid flattening out of mankind's diversity as carried out in a million schools across the globe every day.

Education is destroying humanity, one ‘small people’ at a time.

Language death is probably the best metric we have to measure the dramatic speed at which the deliberate destruction of human diversity is taking place – a destruction that in many ways resembles, and in many places actually goes hand in hand with, that of the diverse physical environments in which humanity has flourished over the past few tens of thousands of years.

According to Ethnologue, there are 7,139 officially known languages in the world.

Of these languages, 3,193 are endangered today: that is, an astonishing 45% of them.

But this underestimates real problem. There are only 193 officially recognised countries (194 if we include Palestine, which, of course, we all should!) in the world today.

And, with very few exceptions (shout out to the Plurinational State of Bolivia here!), these countries are nation-states that, like all nation-states, overwhelmingly seek to privilege their own state language above all the others spoken within their territories, at the (often-fatal) cost of those other languages.

What we’re looking at, then, is a world in which, if these 194 nation-states had their way and their ‘official’ languages remained the only ones spoken in their territories, the other 6,945 languages currently spoken in the world today would end up going extinct; a reduction in the world’s linguistic diversity of just over 97%.

However, the reality is actually far worse than that. Many of these 194 countries actually have the same official language: by a quick, crude, Wikipedia-based reckoning, 21 of them have Spanish as an official or co-official language; 25 countries have Arabic; 27 have French; and 31 countries have English as both an official language of state and the primary language (or at least the lingua franca) of much of, if not all of, the population.

Now, to do some even more crude maths, if we take into account the prevalence of these 4 ‘global’ languages, then there are actually only 90-something different ‘state languages’ in the world today.

This means that if all the other ‘unofficial’ languages spoken in the territories of these nation-states disappear, leaving in their place a single, solitary ‘official’ language as the entire population’s means of communication, the number of languages in existence would drop from 7,139 to around 90: a decline in humanity’s linguistic diversity of almost 99% from where we are today.

We are facing not just mass extinctions of plants and animals; the world is also on the brink of a mass extinction of the linguistic diversity that, for as long as we have been a distinct species of ape, has been one of our defining features as Homo sapiens: the thinking ape.

This mass extinction is, of course - like all the others currently threatening the complex, interlocking ecosystems that make up the world in which we live - inextricably tied up with the last 500 years of destructive, European-led imperialism and colonialism.

Empires, Nation-States and ‘Linguistic Imperialism’

The global prevalence of Spanish, French and, above all, English is no coincidence: the empires carved out by speakers of these languages resulted in both the direct and indirect deaths of at the very least hundreds of millions of people. With them died the unique languages and cultures of hundreds if not thousands of different tribes, peoples, nations; hundreds if not thousands of ways of understanding and relating to and being on and with the lands in which their otherness had evolved over the centuries.

But language extinction has a far deeper history than that: the Ancient Greeks, Han-dynasty China, the Romans, the Persians, the early Islamic empire, the Mongols – all of them were responsible, whether deliberately or as an unwitting side-effect of imperial expansion, for the deaths of the languages of many of the peoples they conquered.

And ironically the rate of language extinction has only risen in the years since the days of the great empires, whether Roman or Muslim or Spanish or British, came to an end, and in their place came the rise of the nation-state, with their roads and schools and aggressive nationalist ideologies that combine the worst impulses of the old ‘civilising’ imperialisms with the newer language of Liberalism.

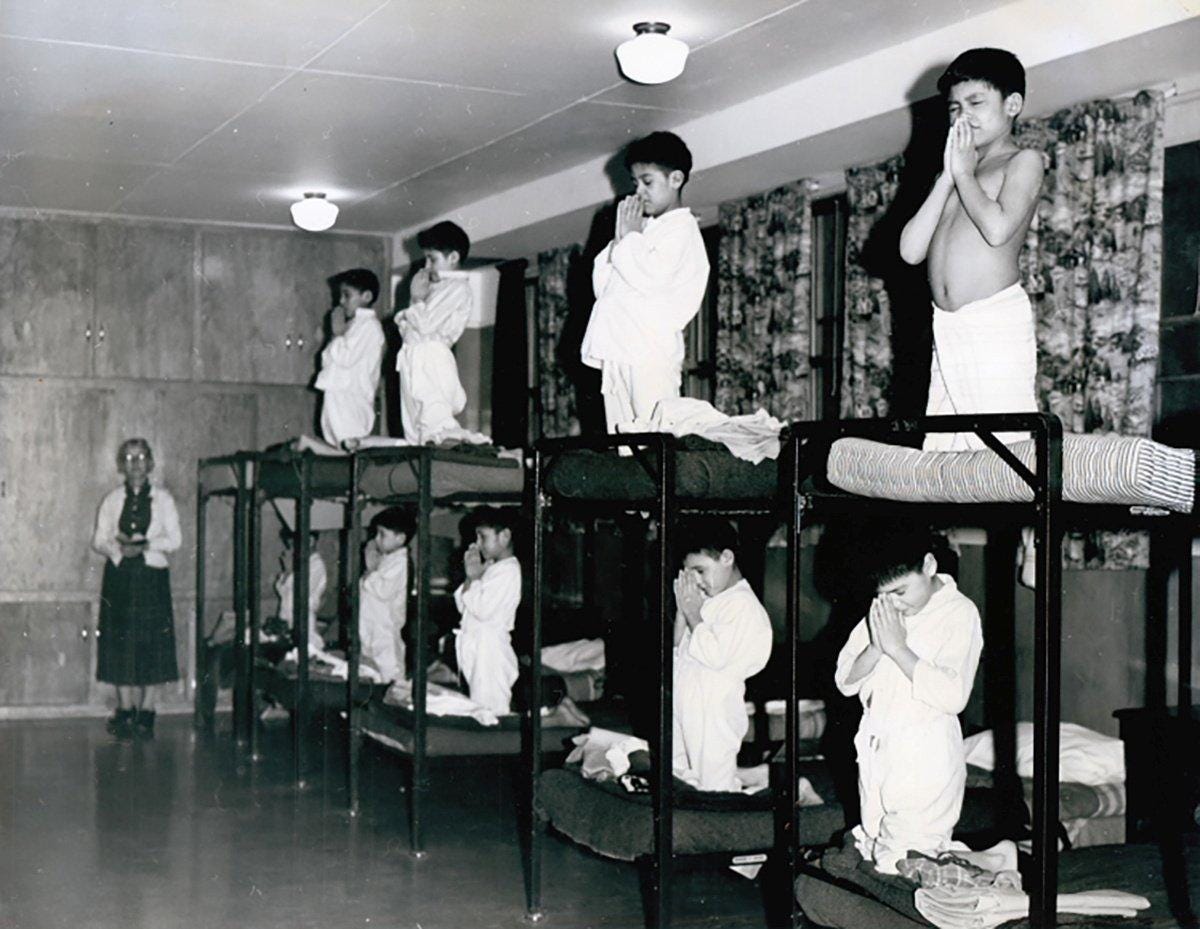

Cases of school-induced language death are particularly prevalent in the anglosphere, aka the successor states to the British Empire, where in recent years they have inspired at least a bit of (often token) soul-searching: Canada and Australia, in particular, have been home to government-backed truth commissions and vigorous public debates over the legacy of the squalid government-funded boarding schools established for Indigenous/First Nations/Aboriginal children after independence from Britain.

These children – known in Australia today as ‘the Stolen Generation’ – were often literally ripped from the arms of their parents and taken off for re-education at the hands of ‘Christian’ child abusers and tyrants. The mass graves now being uncovered on the sites of these facilities speak for themselves. So does the Canadian state's recent agreement to pay $2.09 billion USD (£1.68bn) ‘to settle a class-action lawsuit seeking compensation for the loss of language and culture caused by its residential school system,’ which it has acknowledged as part of ‘a policy of cultural genocide.’

The US, too, was apparently beginning to wrestle with this unsavoury aspect of its recent history, which saw, according to this fascinating episode of

’s Skipped History substack with Red Cliff Band Ojibwe journalist and historian Mary Annette Pember, ‘about 76% of Indian children, some as young as four years old,’ forced to attend so-called ‘residential schools’ by the 1920s, where they were routinely brutalised, caught tuberculosis and ‘mainly did a lot of hard manual labor. They were trained to be maybe servants or farmhands, the only kinds of positions they felt that we were qualified for.’ You can check out the whole episode here - I highly recommend it!Unfortunately, of course, it’s unlikely that any state-backed reappraisal of the ‘residential schools’ will survive the country’s current descent into fascism, and they’ll likely go straight back into the country’s skeleton-filled closet along with other, cheery things like the US government’s active genocide of about 90% of the Native population (which I’m afraid no amount of ‘land acknowledgements’ are ever going to make up for. Sorry!)

Shared Histories of Cultural Destruction

In many ways, the use of schools to try to destroy what was left of Native civilisation in these places reflects their shared heritage with Britain, where similar policies were applied to the Gaelic-speaking Scots from the seventeenth century onwards, initially in order – ironically – to cement the Scottish King James VI’s claim to the English throne.

Gaelic was seen as one of the causes of the frequent rebellions in the Scottish Highlands and Islands that threatened James’ Scottish base and, by extension, his rule over the rest of what would soon become the UK; it was also associated with the Catholicism that posed a similar challenge to the legitimacy of the Protestant branch of the royal Stuart family.

The solution was the introduction of the Statutes of Iona in 1609, which ‘required that Highland Scottish clan chiefs send their heirs to Lowland Scotland to be educated in English-speaking Protestant schools.’

Many more state-sponsored anti-Gaelic education initiatives followed over the next couple of hundred years, and today speakers of Scots Gaelic make up only 1.3% of the Scottish population, down from 22.9% in 1755.

Soon after, the British government began using similar policies to target the Irish and Welsh languages. Abusive and culturally imperialist education programmes turned Welsh from a majority to minority language in the space of a few generations; in Ireland the application of similar policies, combined with the famine, mass migration and violent religious repression that characterised life there under the British occupation, saw a reduction in the number of monoglot Irish speakers from 800,000 in 1800, to under 17,000 by 1911.

But it wasn’t just monarchies that inflicted these kinds of policies on their subjects.

The French Republic did almost exactly the same thing shortly after chopping off the king’s head, as part of a campaign to centralise political control of an until-then diverse country in which much of the population spoke their own, local languages – Basque, Breton, Occitan, Gascon and various others – rather than the ‘French’ that dominated in Paris.

Nor was it only great empires like Britain and France that employed imperial techniques internally.

Italy in the late 1940s had only existed as a state for about 70 years and had just emerged from the chaos, disruption and occupation of the Second World War. But, enfeebled as it was, its Christian Democrat government still picked up directly where the Fascists had left off by embarking on a concerted programme of cultural and linguistic assimilation that successfully pressured speakers of Sardinian, in particular, to abandon their ancient heritage in the name of ‘modernisation.’

And, despite this point dragging me into some ridiculous, bad-faith beef right here on this very site the other month, even the Bolsheviks soon backtracked on initially radical korenizatsiya (‘indigenization’) policies designed to empower the many non-Russian peoples of the USSR, and only a decade or so after coming to power began once again to enforce a programme of cultural and linguistic ‘Russianization’ little distinguishable from its Tsarist predecessor.

Evidently, linguistic imperialism is an impulse that trumps ideology, chronology, and geography.

And it’s not just an imperial phenomenon either.

Ironically, linguistic imperialism is also just as prevalent in post-colonial states – which today exercise practical day-today control over a far greater area of the globe than the old empires ever did, meaning that these states’ policies also affect more of the world’s population.

In India, education programmes for ‘Tribal’ children have long been organised along exactly the same lines as the schools for Native and First Nations children in the US and Canada.

Even supposedly more ‘enlightened’ initiatives have been criticised by anthropologists like Malvika Gupta and Felix Padel as attempting

to ‘convert’ children in two related senses: one, by instilling an ideology of industrialization in a process comparable with religious conversion… and second, by transitioning children from land-based families to participants in an industrial workforce in mining projects that are extracting land from tribal ownership or occupancy.

Gupta and Padel’s report focused on the privately-run ‘Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences’: the world’s largest boarding school and an institution ‘that some people within India’s government promote as the new model of tribal education.’

Here, children from a wide range of Odisha state’s 62 different Adivasi peoples

dress in blue and pink uniforms, their hair is cut short, and no traditional ornaments are allowed—just as tribal knowledge and value systems find little place in what is taught. Children reportedly stay without a break for 10 months a year and, we were told, have limited contact with their families. Specifically, parents report that when they are permitted to visit, they are not allowed to enter their children’s hostels and that children arriving back at school after the summer break have their bags scrutinized for any food brought from home, which is forbidden and thrown away in front of them as ‘unhygienic.’

And of course, as part of their ‘education,’ the children at the school

have to adapt to a new language, usually the dominant state language. Exclusion of tribal languages from most of India’s tribal schools has contributed to the diminishing use of several hundred ancient tribal languages, which some scholars have termed “linguistic genocide” in similar contexts. This is a tremendous loss in that each such language encapsulates a unique worldview.

Similar initiatives have become commonplace in China, too.

Here, naturally, boarding schools are controlled by the state, rather than private companies. But their aim is exactly the same: to forcibly assimilate ‘troublesome’ minorities into the national mainstream.

As part of the Han-dominated Chinese state’s attempts to enforce its will on the long-suffering Uyghur people of Xinjiang, for example, in 2023 three independent human rights experts working for the UN denounced what they described as the

large-scale removal of youngsters from their families, including very young children whose parents are in exile or “interned”/detained. The children are treated as “orphans” by State authorities and placed in full-time boarding schools, pre-schools, or orphanages where Mandarin is almost exclusively used.

According to the experts,

Uyghur and other minority children in highly regulated and controlled boarding institutions may have little interaction with their parents, extended family or communities for much of their youth. This will inevitably lead to a loss of connection with their families and communities and undermine their ties to their cultural, religious and linguistic identities.

But… Why Should I Care?

Well for a start, you should always back the underdog. It’s a matter of principle. And who could be more of an underdog than the speaker of an endangered language facing up to the entire might of a state determined to rip that away from them and their children by any means necessary?

Second, if you care about the state of the planet, then you should support the right of local communities to control their own lands and resources. Time and time again, Indigenous peoples in particular have been proven to be the best custodians of the environments in which they live and the riches therein.

Indeed, this is exactly why so many nation-states have been and continue to be so determined to wipe these same peoples from the map and deliver the resultant, ‘empty’ lands into the hands of those who will exploit them more ‘efficiently’: that is, in ways that conform to the logic of capitalism and the interests of ‘national’ elites rather than local populations who make the most of their environments with the long-term survival of everyone in mind.

And the fact is, you can’t have territorial autonomy without cultural autonomy, too - for if a people ceases to be, then how can they keep caring for their land?

For this reason, standing against the destruction of the diversity of humanity’s languages and cultures is vital to challenging the entirety of the destruction currently taking place across the globe: from the upending of the climate to the decimating of the forests, the pollution and overfishing of seas and the dredging of rivers, the open cast mines devouring whole mountains and the slaughter of all of the beings that give life to these places.

Which leads to the third and most important point of all: each language, each culture, is a world in itself, a way of being, seeing, doing, understanding the world and all that is in it, of organising people and structuring whole philosophies and ideologies, often in ways totally alien to the handful of cultures - the real minority cultures if we’re being totally objective - that gave rise to today’s rapacious global capitalism and that seem, in turn, increasingly impossible to decouple from it.

No man is an island, nor are cultures and identities remote atolls. But not all are totally interconnected - far less equally interchangeable - either.

Each language is a unique contribution to humanity, a star in the diverse constellation that is mankind.

Every time one of those stars is extinguished, we lose a chunk of what makes humanity so fascinating - not to mention a set of ideas that might help to guide us out of the mess that we find ourselves in as a species right now, and point way to a better future for all of us.

Thank you for this piece, it was devastatingly sharp. As a philosopher trained within these very systems, I often wrestle with how deeply the epistemologies of domination have shaped, well, everything... Your piece left me thinking: what forms of knowing, of sensing, of becoming-with the world are we still unable to access? not because they’re "lost", but because they've been systematically erased, and we’ve been trained not to recognize them as valid, or even as real?

For those of us working toward systems change, what you write about here is a sobering reminder: if we don’t actively protect and co-create plural knowledge systems we are not offering a real alternative.