Finding Joy in the Apocalypse

It might not be a ‘revolutionary act’ but it’s sure as hell gonna be necessary. Indigenous peoples help us to see why.

I probably don’t need to tell you that everything is fucked. It turns out the ‘vibe shift’ was towards doom. This might actually be the beginning of the end of the world.

But you know who survived an apocalypse before?

Literally every single Indigenous people still in existence.

Pandemics, enslavement, conquest by fire and sword, the theft of their lands, their gods, and in many cases even their children. We’re talking properly apocalyptic stuff here.

And for most of them, things haven’t got all that better since the arrival of the crusaders, the conquistadors, the slavers, the redcoats, or whoever else fucked it all up for them the first time round. Civil wars, drug wars, ethnic cleansing, forced assimilation through re-education: you name it, they’ve been through it, and they’re probably still going through it.

And yet… you know who also loves a good party?

Literally every single Indigenous people still in existence.

All of them possess unique and distinctive and incredibly rich sets of ritual, ceremonial, religious, social - and even political and economic! - practices that involve, at least on some level, having fun.

Whether it’s clearing a field for planting, initiating a new member of a community, commemorating births or deaths or giving thanks for a successful hunt, a successful harvest or, nowadays, a successful application for funding from some well-meaning NGO: all are likely to involve, at some point, drinking, joking, dancing; music, laughter, life.

This a key part of what keeps those practices alive in the first place - the fact that they’re not just useful, or grounding, or good for the environment or the pueblo or the deified ancestors, they’re also enjoyable.

Now, this isn’t to romanticise life in Indigenous communities today. They’ve got just as many problems as the rest of us - and often more, given all the aforementioned crises that so many of them are still living through today on top of everything else.

Nor do I want to lend undue credence to the idea that “having fun” and “finding joy” and “performing self-care” is always and inherently a genuinely “revolutionary” act.

It’s an idea that seems to have birthed a whole sub-genre of writing here on Substack. Some of it, especially when it comes from people whose very existence entails ‘resistance,’ is interesting and insightful and valuable. And some of it, especially when it comes from lazy pseudo-activist liberals who believe that the new age meditation practices they’re also writing about on Linkedin will somehow put a stop to climate change, is deeply, deeply cringe.

And in the end I’m afraid I’m probably with

when, in this powerfully argued essay on the strength - or weakness - of 'slogans,’ he argues thatResistance is a word inseparable from radical struggle—it is how revolutionaries articulate their fight against oppressors. Resistance requires the activity of confronting injustice, it requires a spiritual voltage that’ll grant its inhabitants the courage to look snarling beasts in the face while fear quakes in their chest and so I believe slogans balancing equations such as rest as resistance are pacifiers. A call-to-action that calls for inaction is no call at all. Equating resistance with virtues like joy/rest/love do all of the concepts involved a painful disservice to each other.

Check the whole piece out here - it’s a banger!

But even if we can’t just celebrate the apocalypse into submission, nor can we only focus on our

or give in to

Feeding our souls isn’t gonna win us a new world on its own; but if it’s harder to fight on an empty stomach, then it’s positively dangerous to try and change the world while you’re feeling empty inside.

And at the end of the day, the staying power of so many Indigenous communities that practice direct democracy and/or live in relative balance with their ecosystems and/or believe that unbridled consumption is dangerous - all of which has involved them fighting and enduring and even managing to win so many of their own revolutions in the midst of so many different apocalypses - attests to the importance of joy as a survival mechanism.

So… I don’t have any more insightful and well-argued (lol!) political arguments to present to you all this week.

Instead of pondering such things, these last few days I’ve been limiting myself to watching the world burn out of the corner of only one eye, while doubling down on my actual work as a historian and writer and anthropologist and, in my own small way, advocate for the Indigenous peoples of Mexico in the face of a decaying world-system that remains desperate to wipe them off the map.

(If you’re interested in any of that, btw, then do consider subscribing now!)

For the last fifteen years, this work has involved close collaboration with members of the Wixarika, Naayari, O’dam and Meshikan peoples of the western Mexican mountains (also known as Huichols, Coras, Tepehuanos and Mexicaneros).

They’ve survived multiple apocalypses already and they’re still here, still alive, and still having some fucking banging fiestas while they’re at it.

Today, I want to share some of that with you (and anyone else that you want to share it with, too - just hit the button!)

So, without further ado, here are some photos of Indigenous joy, as I had the privilege of experiencing while researching and writing my first book, on how the Indigenous communities of Mexico’s Sierra Madre mountains made the Mexican Revolution - the first of the great social revolutions of the twentieth century – their own.

Starting with:

Naayari ‘devils’ taking part in some entirely pagan Easter Week festivities

The Naayari Easter Week is a particular banger. A struggle between light and darkness, the forces of unsustainably austere moral purity versus out-of-control, destructive fertility. A deeply political ‘religious’ event, then: unsurprising, given just how intertwined the two are in Naayari, Wixarika, O’dam and Meshikan society, where religious beliefs, rituals, prayers, fiestas and thanksgivings still permeate every aspect of local life, from farming and hunting to politics and warfare…

… not to mention history, including the stuff I was researching: narratives of the Mexican Revolution are deeply embedded in modern ceremonial practices, as you can see above in the form of the bandolier-draped “devils” escorting the “Centurion of Darkness” as he takes over the pueblo of Santa Teresa bang in the middle of Holy Week.

It was all so mind-blowing that I signed myself up for a mandatory five-year ritual commitment as a participant. Helping to prepare ritual feasts, dancing, praying, drinking, running laps of the pueblo and fighting other stick-wielding “devils” helped me to understand how local rituals express and help to preserve collective memories and more far-reaching mythical-historical narratives, all of which have been inflected to some degree by local participation in the Mexican Revolution.

Rodeos and cockfights, where craic trumps ceremony

It wasn’t just fiestas imbued with deep religious and historical meanings that I found myself in the midst of. There were rodeos, as you can see above; and epic horse-races in the mud, followed by much needed fag-breaks.

And, as you can see below, there were cockfights, too, just for the hell of it: about as secular an event as you can get, all about the beers and the thrill of gambling.

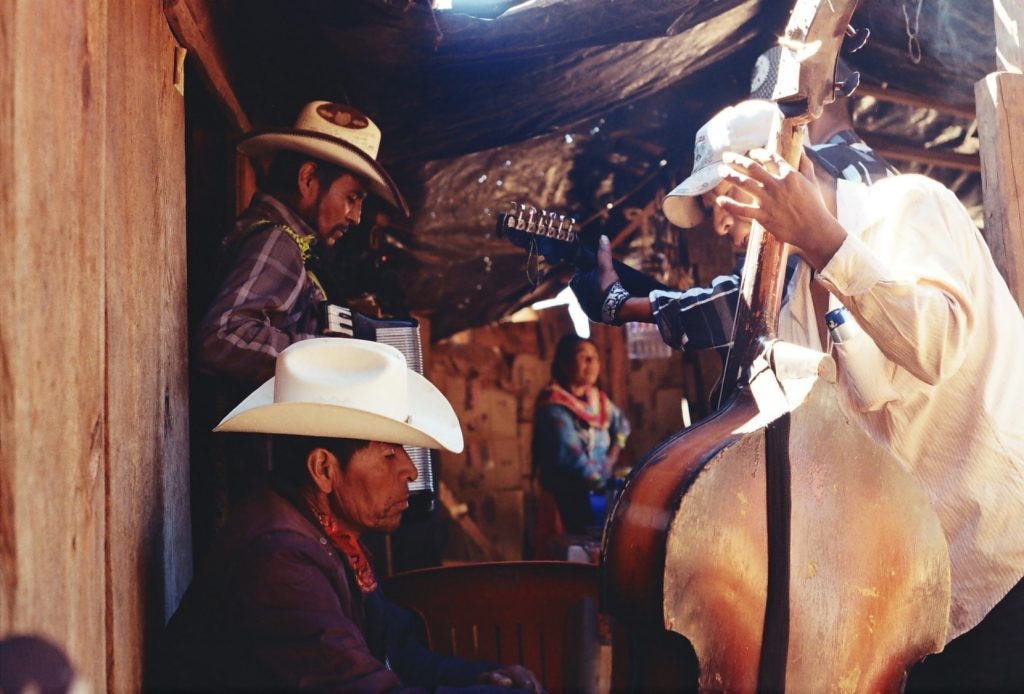

Music is always part of it…

Above, a Naayari violinist accompanies -or maybe it’s more accurate to say, duets with - a woman dancing on a tarima, a hollow, rough-hewn, resonant wooden block that amplifies the rhythmic movement of her feet.

Below, a Wixarika musician plays on his own, home-made violincito - 'little violin’ - in the midst of a communal celebration in San Miguel Huaxtita.

And here you have another group of Wixarika musicians about to rock a street corner on the sidelines of a fiesta in a different village. Much more important to local people than the hand-painted political advert for the conservative PAN party on the wall behind them…

… indeed, many of the Indigenous communities of Mexico, including some of the neighbouring Wixarika pueblos, have banned political parties outright as a source of corruption and conflict that undermines traditional, consensus-based and ritually-legitimised local forms of direct democracy.

… And so is family.

I think these last few images speak for themselves, really. Different generations, children and women and men, standing together, doing their thing, living their cultures, being themselves. It might not be enough to overthrow Trump or Putin, but it’ll outlast all of the bastards. It might even help the rest of us head in a better direction once they’re gone.

If you made it all the way down here, then thanks very much for reading!

If you liked what you read and you haven’t already signed up for more, then you can do that right here:

Or you might consider leaving some of your thoughts in the comments - I’d love to hear them.

Meanwhile, last but not least… all my writing is free and will remain free in the foreseeable future. It’s not about the money - it’s about the hope that maybe, in some small way, my words might have a positive impact on this benighted world of ours. Sharing them makes that more likely! 🙏

That's a really nice piece! Not dancing at the end of the world, but dancing against the end of the world? I like it :)