I finally went back to work this week after a full month of paternity leave. And so it was inevitable that my entire family would be ill this week: my eldest son was off nursery with a nasty cough for two days while my wife snuffled away on the sofa, trying to push through a horrific sinus headache for long enough to feed a grizzly month-old baby enjoying his first ever cold, as I did the rounds with soup, tea, cough syrup, Calpol... A perfect time, then, for me to have accepted a commission to write a short article on the Mexican government’s relationship with drug traffickers for The Conversation, on top of trying to get back into the swing of my ongoing book project and a couple of much-delayed academic papers.

Still – it’s now Friday, my son’s recovered, my wife and baby are feeling well enough to have gone for a nice long walk in the drizzling London rain, and it’s now me who’s got the sinus headache… as well as, by some miracle, a finished article for The Conversation that’ll be hitting the internet early next week. Which means that I can now share with you a slightly expanded and, in my mind, more elegant version of the same piece which, at only 1,200 words, is still short and sweet enough to be easily digested in a single sitting. And so, without any further ado, here’s the answer to the question you’ve all been asking yourselves:

Is the Mexican Government Really in Bed With Drug Cartels?

A few weeks ago the US president, Donald Trump, asserted that the government of Mexico has formed an “intolerable alliance” with the country’s drug-trafficking organisations. His remarks have cast a pall over bilateral relations already strained by recent talk of tariffs and military interventions against cartels now officially designated as terrorist organisations.

Although the two nations have sometimes clashed in the past, Mexico is today a close US ally and its top trading partner, with total two-way commerce totalling $807 billion USD in 2023. Joint US-Mexican anti-narcotics collaborations stretch back nearly a century, and most recently include US backing for the Mexican government’s ongoing ‘war’ against the cartels (which has resulted in nearly half a million deaths and disappearances since its launch in 2006).

Trump’s accusation was therefore as unexpected as it was explosive.

So much so that it brought figures from across the Mexican political spectrum together in condemnation of what Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum has dismissed as ‘baseless slander.’

However, while the Mexican government is the ultimate upholder of the country’s strong prohibitions against the production and trafficking of drugs like marihuana, methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin and fentanyl, and is therefore on paper a resolute enemy of the drug trade, the undeniable existence of drug-related corruption in Mexico means the reality is a little more complex.

The Mexican Political System and Drug-Related Corruption

Although Trump refers to ‘the government of Mexico’ as though it were one, unified body, it is divided between municipal, state and federal levels, and between executive, legislative and judicial branches. When it comes to enforcing Mexico’s constitutional prohibitions on drugs, responsibility in any one area of the country has historically been shared between municipal, state and federal institutions, all under the command of different officials with different organisational – or, indeed, personal – agendas.

This complex situation of overlapping authority has facilitated a long history of collaboration between drug traffickers and particular elements of the Mexican government, which have varied wildly from place to place, operated at vastly different scales, and changed greatly over time. For just as the word ‘government’ belies the enormous complexity of the Mexican political system, so too the word ‘alliance’ oversimplifies the many different forms of drug-related corruption that have existed in Mexico over the years.

Low-Level Corruption and Indirect Government Involvement

Since the birth of the Mexico-US drug trade in the early twentieth century, individual government officials have turned a blind eye to the activities of drug traffickers in exchange for bribes. This is what we might call ‘indirect’ government involvement in the drug trade, and has always been by far the most prevalent form of drug-related corruption in Mexico.

In a previous article for The Conversation - an extended version of which I also published right here on Substack the other week - I explored how from the 1930s onwards, political bosses, police chiefs and military commanders in the so-called ‘Golden Triangle’ states of Sinaloa, Durango and Chihuahua taxed illicit opium production in the areas under their authority, and sabotaged anti-drugs campaigns waged by other branches of government. In so doing they avoided conflict with their (often heavily-armed) constituents, and took a healthy cut of the profits that the opium trade was already making for these local narco-pioneers.

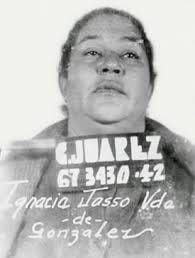

My fellow historian and close friend Benjamin T. Smith has written plenty about the similar intrigues that likewise took place in the main trafficking hubs on the US-Mexican border, like Tijuana, Ciudad Juarez and Nuevo Laredo. These involved, amongst others, Ignacia Jasso alias ‘La Nacha,’ Mexico’s first ever female drug lord (drug lady?), who in the 1930s founded an important early drug cartel that continued to control much of the drug trade in Juárez until the 1970s.

As both Mexican and US drug enforcement efforts created an ever more profitable black market over the second half of the twentieth century, low-level corruption accompanied the expansion of drug production and trafficking south into other areas of Mexico like Nayarit, Michoacán and Guerrero.

Today, the indirect involvement of local representatives of the Mexican government in the drug trade has become a fact of life in such places.

But zones of drug production and/or trafficking still constitute only a fraction of Mexico’s total territory, meaning that local officials with the opportunity to engage in such corruption comprise a tiny minority of the overall government workforce.

High-Level Corruption and Direct Government Involvement

There are also cases, however, in which higher-level representatives of the Mexican state, or even entire government institutions, have participated directly in the production, transport and/or sale of illegal drugs. Although such cases are relatively rare, they are also inherently higher-profile than the more routine, ‘looking the other way’ kind of corruption, and are therefore more likely to make headlines in the US and from there inform popular and even national political discourse.

The earliest such case is likely that of revolutionary military commander Esteban Cantú, who constructed a powerful, personalist political regime and funded important local development projects in the northern state of Baja California between 1915 and 1920 ‘by taxing the import, sale, and production of smoking opium first legally and then, when President Venustiano Carranza banned the practice, illegally.’

Such high-level involvement in the drug trade became more frequent as the trade itself became ever more illicit and ever more profitable. In 1940, Governor Rodolfo Loaiza of Sinaloa cut a series of deals with the up-and-coming drug trafficking organisations of his native state, before an attempt to double-cross them cost him his life in 1944. Around the same time, political campaign manager Carlos Serrano looked to regional drug smugglers to help fund Miguel Alemán’s successful run for the presidency, after which Serrano moved directly into opium trafficking himself via his command of the newly-created Federal Directorate of Security (DFS), a US-sponsored anti-communist secret police force that attacked smaller traffickers and took their business under the cover of the government’s new ‘permanent campaign’ against the drug trade.

After President Nixon declared a ‘war on drugs’ on both sides of the border in 1971, increasing anti-drug crackdowns provided more opportunities for the same Mexican officials charged with enforcing prohibition to cut deals with traffickers, while resultant squeezes on supply caused prices to soar and made such deals ever more lucrative for low-paid government officials. By the mid-1980s, the DFS as an institution had become so deeply immersed in the drug trade that several of its agents were implicated in the murder of DEA agent Kike Camarena, and the agency itself was disbanded soon after.

But as US demand for marihuana, methamphetamine, heroin and especially cocaine continued unabated through the 1990s and into the twenty-first century, the profits offered by involvement in the drug trade proved hard to resist for a select number of high-ranking government officials, including members of the federal cabinet, state governors, and even the architect of Mexico’s ongoing, US-sponsored ‘war on the cartels,’ Genaro García Luna, now serving 38 years in a US prison for colluding with ‘El Chapo’ Guzman’s Sinaloa Cartel.

An ‘Intolerable Alliance’?

However, the indirect involvement of government officials on an individual level remains far more common than direct or institutional involvement in the drug trade. Such corruption is largely opportunistic, rather than systematic, as evidenced by its continued concentration in areas of Mexico where drug production and trafficking are particularly prevalent.

And it should also be noted that such corruption is not only limited to the Mexican side of the border, either: US investigations show that plenty of crooked American cops and politicians have cut deals with traffickers over the years, too.

Trump’s recent attacks on the Mexican government are therefore more of a headline-grabbing shot across the bows in the context of an ongoing renegotiation of many different aspects of US-Mexican relations, than an accurate diagnosis of a uniquely Mexican problem.

In the end, the issue of drug-related corruption in Mexico has less to do with its own government and more to do with American society’s own insatiable demand for drugs. Crackdowns on the cartels ultimately cause the price of drugs to go up, increasing the temptation for Mexican officials to try and grab a piece of the pie.

As a businessman like Trump should be able to see, it’s not government corruption that drives the US-Mexican drug trade, but the iron laws of supply and demand.