Man, last week was a lot.

Trump wants to ethnically cleanse Gaza and turn it into a golf course. What? Musk has abolished USAid, setting the cause of American ‘soft power’ back about a century. What?? Tariffs are back in style - not so much with trade rivals but with trade partners - but, erm, actually, not ‘til next month. What?! Cartels are terrorists; the Panama Canal is American; half the world is literally on fire but at least Prince Harry isn’t going to be deported after all. Whaaaat?!

To be honest it was all so much that, when combined with looking after a three-week old baby and a three-year old kid, I found it impossible to properly process the sheer volume of batshit madness spewing out of the US into the rest of the world last week, meaning that this post will necessarily be a bit shorter than the last couple were.

But the simple fact that there’s been too much going on out there for me to digest is, in itself, worth reflecting on.

Which is a long-winded but necessary prelude to the main point of this post: that is, if it wasn’t already clear to everyone from the events of the last few years, then the events of last week alone are undeniable evidence that the era of ‘the end of history’ is over.

So… We’re now living the End of the End of History?

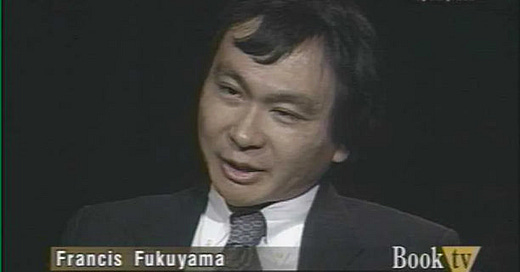

Well, the idea that history ever ‘ended’ was bullshit from the start, of course. But it was also persuasive bullshit. First dreamed up by Francis Fukuyama in an article in 1989 and further developed in a follow-up book in 1992, the idea - which the good professor has been dining out on intellectually and financially ever since - was that the fall of the Berlin wall and subsequent collapse of the USSR marked

‘not just the end of the cold war, or a passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalisation of western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.’

This neat little idea - almost Victorian in its jingoistic whiggishness - went on to enjoy an illustrious history (if that is still the right word?) as a self-congratulatory article of faith for smug western elites of both neoliberal and neoconservative persuasions for close to three decades.

However, as noted critic of reductive Liberal bunkum Vladimir I. Lenin (or more likely, it turns out, Mexican poet Homero Aridjis) had already pointed out long before Fukuyama’s big idea captured the imagination of much of the commentariat, "There are decades where nothing happens; and weeks where decades happen."

And just because, in the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall, nothing big enough happened for a couple of decades - despite 9/11, Iraq, Afghanistan, Brexit, Trump 1.0 etc. etc. - to challenge the specific kind of free-market, tech-savvy electoral oligarchy then in fashion in ‘the West,’ that didn’t mean that, well, that that was it: nothing else would ever challenge the world’s linear path towards a permanent era of global peace and prosperity thanks to free trade and free elections.

Oh, the arrogance!

And what fundamental historical ignorance, too - scientific proof that political science is officially the worst of all the academic disciplines (second only, perhaps, to economics - but that’s a post for another day).

Anyway, having ignored all the signs of its imminent demise over the past few decades, even the average New York Times subscriber seems to have finally accepted that Fukuyama’s idea is dead: already dragged down into the swamp of revanchist Russian imperialism, homegrown fascism and live-streamed white-supremacist genocide, the last of its life was finally choked out of it by Trump and co’s recent attempts to buy Greenland, start a global trade war and build a genocide-themed tourist resort and business park complex in Gaza.

Oh yeah. History’s back, bitches!

That’s not to say, though, that all those nice Liberal types - the kind who genuinely kid themselves that the ‘rules-based international order’ was ever actually a ‘thing’ and that capitalist globalisation didn’t just mean swapping child labour in the west for child labour in the east - don’t still have important issues left to resolve. Chief among them are two interconnected questions: 1) how long did history actually ‘end’ for? and 2) when and why did it emerge from hibernation?

In the US, many of the more centrist Democratic faithful seem to believe that history only began again with Trump’s election; although which one of them exactly remains less than clear.

One influential strain of #resistance thought holds that history first kicked into gear again during Trump’s initial presidency, before ending again for a bit while Biden took the reins and then roaring back into life once more with Trump’s victory last November.

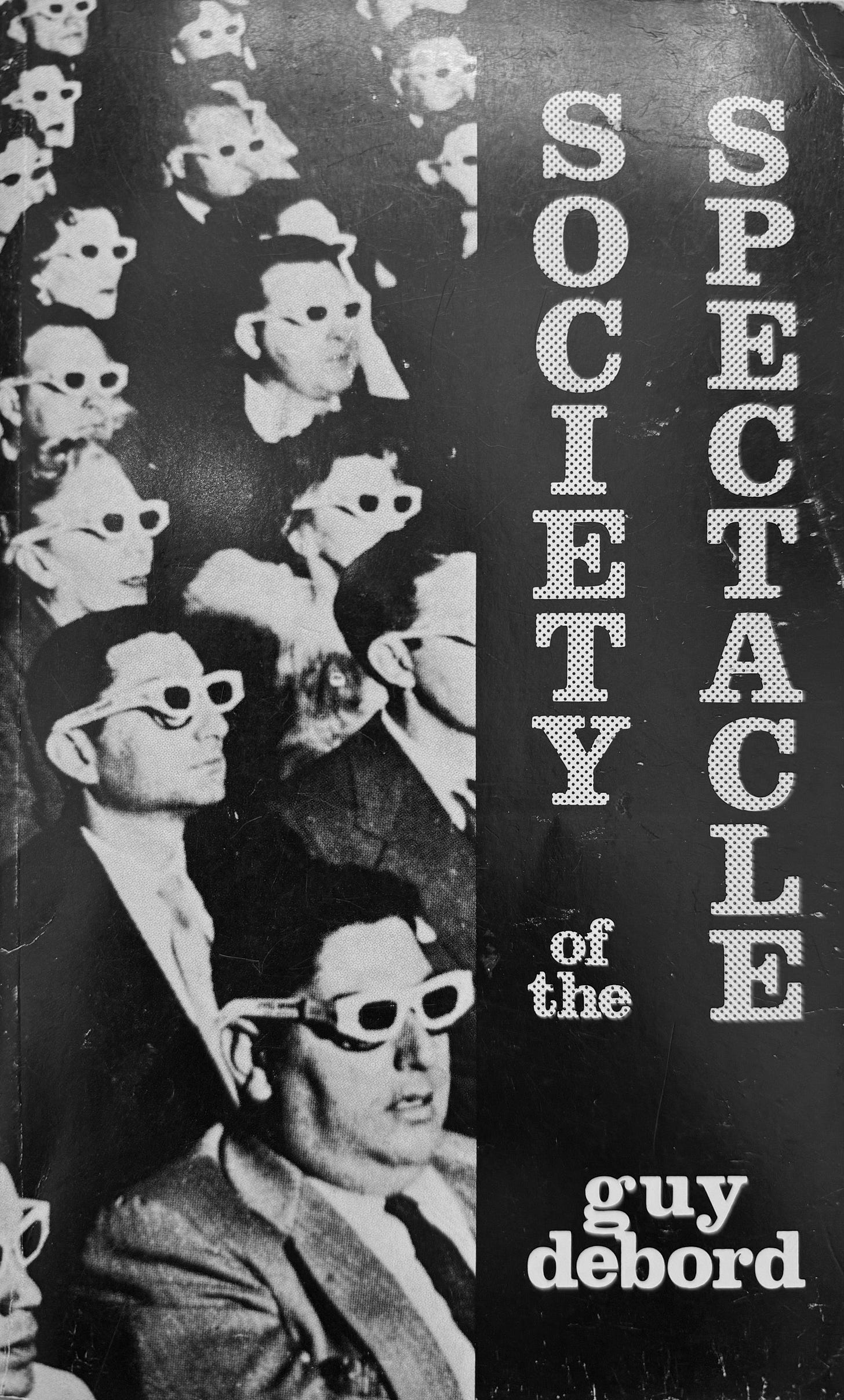

As others on this website have pointed out, this has paved the way for the more ghoulish fundamentalists among them to claim said victory was all the fault of the Palestinians and their supporters, for which they now deserve all the genocide they can get under Trump - with the genocide that already took place under Biden, of course, having rather conveniently occurred in the halcyon days before history began again, meaning that no Sensible™ person should pay any mind to it.

Of course, the genocide in Gaza has also been affected by another distinct set of temporal anomalies. For Team Israel, history began again on October 7th 2023, which conveniently rules out their favourite far-right ethno-state’s constant and well-documented abuses of Palestinian civilians over the previous 76 years as in any way helping provoke Hamas’ attack. An attack that consequently came out of nowhere and for no reason other than the innate antisemitism of the Palestinians (and if you dare suggest otherwise then you’re a Nazi too).

At the same time, however, Trump’s announcement last Tuesday of his plan to ethnically cleanse Gaza “because it’s now too dangerous to live there” means that history must have also paused again for a bit after October 7th - some time between then and last Tuesday, in fact - which is when Gaza mysteriously became an uninhabitable wasteland because of all the bombs that no-one in particular was dropping on it. Which I suppose dovetails nicely with the idea, already mentioned above, that for many Americans, the End of the End of History has happened twice, on both occasions coinciding with election victories for Donald Trump, with Biden’s presidency constituting a kind of Fukuyamist, antihistorical interregnum.

Such phenomena do indeed seem to be influenced by geography, though - Einstein was right, space-time is a thing! - given that, for much of the increasingly fascist British commentariat, history seems to have begun again not with Trump’s election but with Sir Keir Starmer’s, at which point the economy spontaneously became shit, England started losing at football and the high streets magically filled with immigrants and betting shops. Maybe this was when the weather changed for the worse, too? It’s difficult to remember.

Likewise, in my adopted Mexican home, a decent chunk of the middle and upper classes on both the political left and right seem to believe that history - and with it, the corruption, cartel killings and general social and political breakdown now affecting so much of the country - only began with election of the country’s previous president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

And I’m sure the world is full of many more, comparable examples besides.

So… what the hell is going on? Why are Sensible™ people’s memories all so incredibly selective?

Well, call me cynical, but it would all appear to be a tad politically expedient rather a lot of the time. Not to mention better for one’s health - who wants to remember all the shit stuff that happened before? It’d be enough to drive a nice Liberal mad!

But I’ve also been wondering if it goes deeper than that.

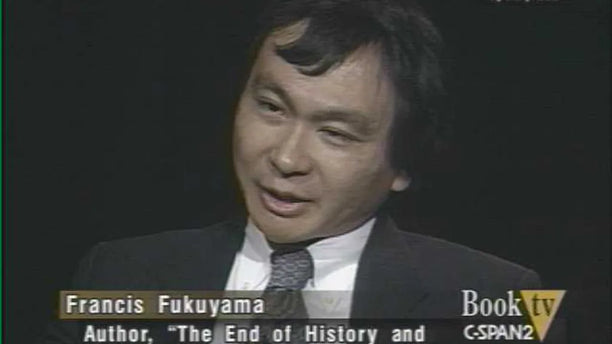

And that’s when I remembered the revolutionary poet-philosopher and political theorist Guy Debord - a man so perceptive that his understanding of the world’s direction of travel drove him to drink, despair and eventual suicide. In 1967, Debord described the emergence and rise to dominance of what Fukuyama defined as ‘Liberal Democracy’ and today’s leftist meme-makers might call ‘Late Capitalism,’ which Debord himself christened ‘the Spectacle’: a political-cultural-economic system in which reality was replaced by images, and "all that once was directly lived has become mere representation." He would’ve been a hit on TikTok, I’m sure.

Anyway, by the late 1980s Debord was arguing that the age of the ultimate form of the ‘spectacle’ was displacing the old ideologies of both the eastern and western blocs and persuading their collective populations to trade in their capacity for complex thought for a ringside seat to a parade of endless, all-encompassing but ultimately empty images.

In the brave new world of what he called the ‘integrated spectacle,’ politics and consumerism had become one and managed to ‘falsify the whole of production and perception, [becoming] the absolute master of memories just as… the unfettered master of plans.’

But the maintenance of this state of things depended on history being successfully abolished and replaced by an endless present:

‘With consummate skill the spectacle organises ignorance of what is about to happen and, immediately afterwards, the forgetting of whatever has nonetheless been understood […] The end of history gives power a welcome break. Success is guaranteed in all its undertakings, or at least the rumour of success.’

For most of the world’s cultures, he continued, history was understood, and valued, as

‘knowledge that should endure and aid in understanding, at least in part, what was to come… In this way history was the measure of genuine novelty. It is in the interests of those who sell novelty at any price to eradicate the means of measuring it. When social significance is attributed only to what is immediate, and to what will be immediate immediately afterwards, always replacing another, identical, immediacy, it can be seen that the uses of the media guarantee a kind of eternity of noisy insignificance.’

In so doing, the system that depends on all of this - the late capitalist global liberal democratic whatever you want to call it that is currently obliterating the world’s Indigenous languages and cultures and digesting and transforming the natural world into homogenous techno-soup inhabited only by mindless phone-zombies - is able, above all,

‘to cover its own tracks - to conceal the very progress of its recent world conquest. Its power already seems familiar, as if it had always been there. All usurpers have shared this aim: to make us forget that they have only just arrived.’ (p.16)

But what if, for all that Trump is in many ways the personification of all of this - the ultimate, attention-economy dominating, industrial-political-cultural spectacle in and of himself - he’s also proving to be just a little too much?

Could Trump be so outrageously noisy and garish and thoughtless and impulsive that he actually risks somehow ‘overloading’ the system of spectacular domination that invisibly imposed itself on the planet after the fall of the Berlin Wall - an occurrence that many of this same system’s unknowing Liberal minions then celebrated with their declarations that history had run its course, and whose undoing they are now similarly picking up on in the form of what they see as history’s sudden return?

It’s certainly true that Trump is doing a pretty amazing job of blowing the spectacle’s cover as he takes us on a nostalgia trip for old school great-power imperialism and the most unembarrassed predatory capitalism since the robber barons: in the end, he’s just not nice enough for polite society to keep pretending that the global halls of power are not actually murderous dens of psychopathy.

Might the spectacle have borne within it the seeds of its own destruction, then, in the form of its own most perfect offspring? Could Trump be late capitalism’s own spectacular antichrist, a curse disguised as a blessing? Or are we just entering another stage of the spectacle’s evolution - one that either Debord did not have time to foresee, or, worse, saw coming so clearly that it took away the last of his hope - in which, on being confronted with our reality’s transformation into a glorified ad campaign, the impetus shifts from the political-industrial complex trying to hide it from us, to our being too busy to look up from our phones to think that things could ever be any different…

In the end, neither is inevitable; the trouble is that now it’s down to us to decide what happens next.